Why Mammography Positioning Techniques Matter for Patient Care

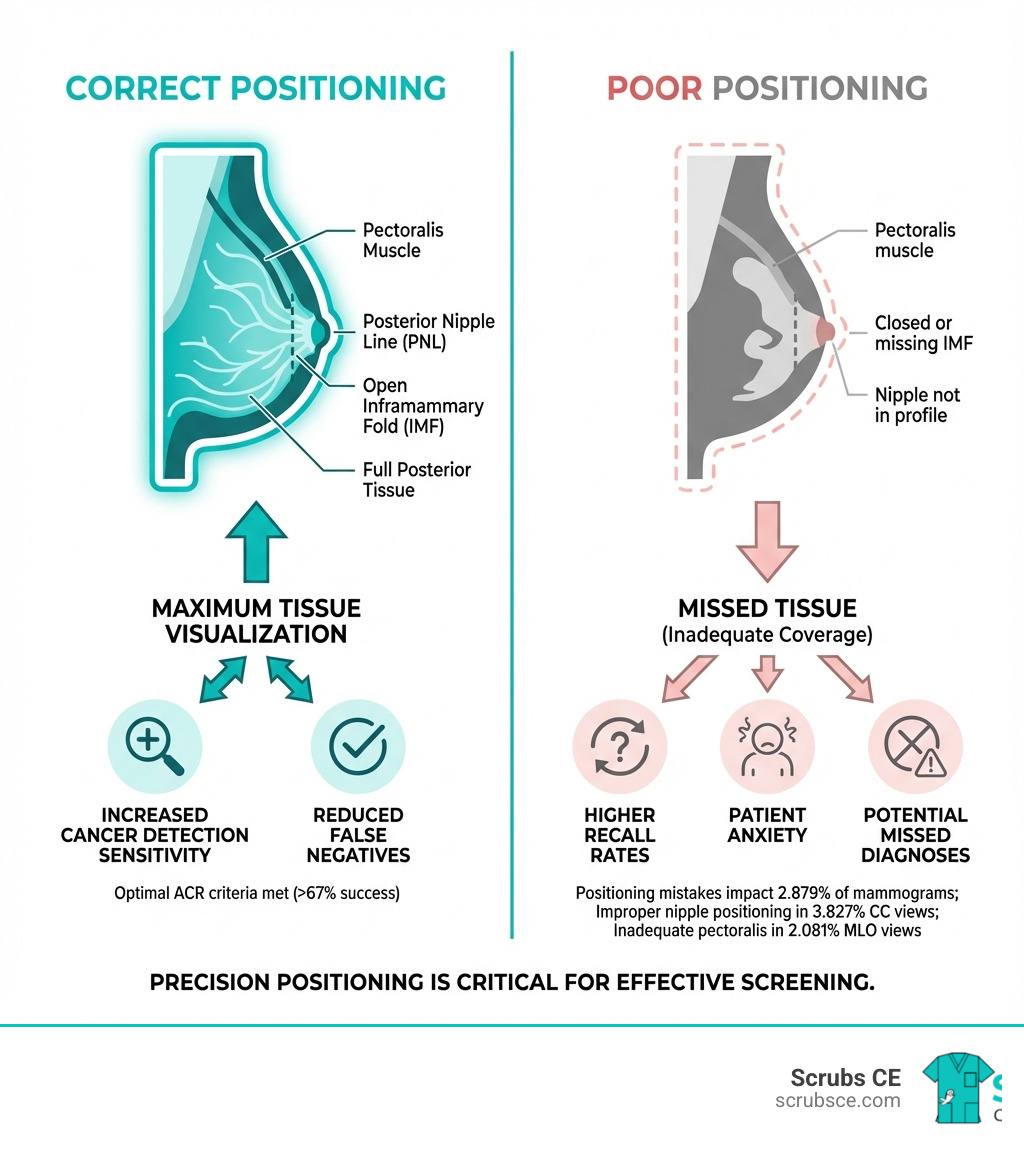

Mammography positioning techniques are the foundation of accurate breast cancer screening. When a radiographer positions a patient correctly, the mammogram captures the maximum amount of breast tissue possible. When positioning is suboptimal, cancers can hide in tissue that never made it onto the image—and no amount of radiologist skill can detect what isn’t there.

The stakes are high:

- 2.879% of mammograms show positioning mistakes that could impact diagnosis

- Improper nipple positioning appears in 3.827% of CC views

- Inadequate pectoralis muscle visualization occurs in 2.081% of MLO views

- Even after ACR positioning training, only 67% of images meet ACR criteria

- Suboptimal positioning directly reduces mammography’s sensitivity for detecting invasive breast cancer

The standard mammography exam requires two views of each breast: the Craniocaudal (CC) view and the Mediolateral Oblique (MLO) view. Each view has specific quality criteria—from visualizing the pectoralis muscle down to the posterior nipple line on the MLO, to ensuring the nipple is in profile on the CC. Missing these landmarks means missing tissue, and potentially missing cancer.

Patient anatomy adds another layer of complexity. Bodies vary enormously—from very large breasts requiring multiple overlapping views, to patients in wheelchairs who need creative positioning solutions, to those with implants requiring specialized displacement techniques. Unlike bone-based radiography where anatomy is standardized, mammography requires technologists to adapt their technique to soft tissue that changes with every patient’s size, shape, and mobility.

Research shows that accepting even borderline positioning increases the likelihood of missing invasive breast cancer. Poor positioning leads to inconclusive exams, unnecessary patient recalls, increased anxiety, and additional radiation exposure from repeat imaging.

I’m Zita Ewert, and through my work leading continuing education at SCRUBS Continuing Education, I’ve trained hundreds of imaging professionals on refining their mammography positioning techniques to meet ACR standards and improve patient outcomes. This guide brings together evidence-based practices and practical solutions to help you master the technical and anatomical challenges of diagnostic mammography.

In the next section, we’ll break down the two standard mammography views—the CC and MLO—and walk through the specific positioning steps that ensure you capture every millimeter of breast tissue.

Mammography positioning techniques glossary:

Mastering the Standard Mammography Views

The journey to flawless mammography begins with mastering the standard views: the Craniocaudal (CC) and Mediolateral Oblique (MLO) views. These are not just arbitrary angles; they are foundational screening views, offering complementary perspectives that are crucial for maximizing tissue capture and ensuring a thorough examination of the breast. Obtaining at least two views of the breast is essential because it allows for more breast tissue to be imaged, provides a more comprehensive screening exam, and offers better localization of any underlying abnormalities. As you can imagine, a single view simply can’t capture everything, and research has shown that single-view mammography can lead to 11% to 25% of cancers being missed!

For those looking to deepen their expertise, consider exploring more information about mammography technologist training.

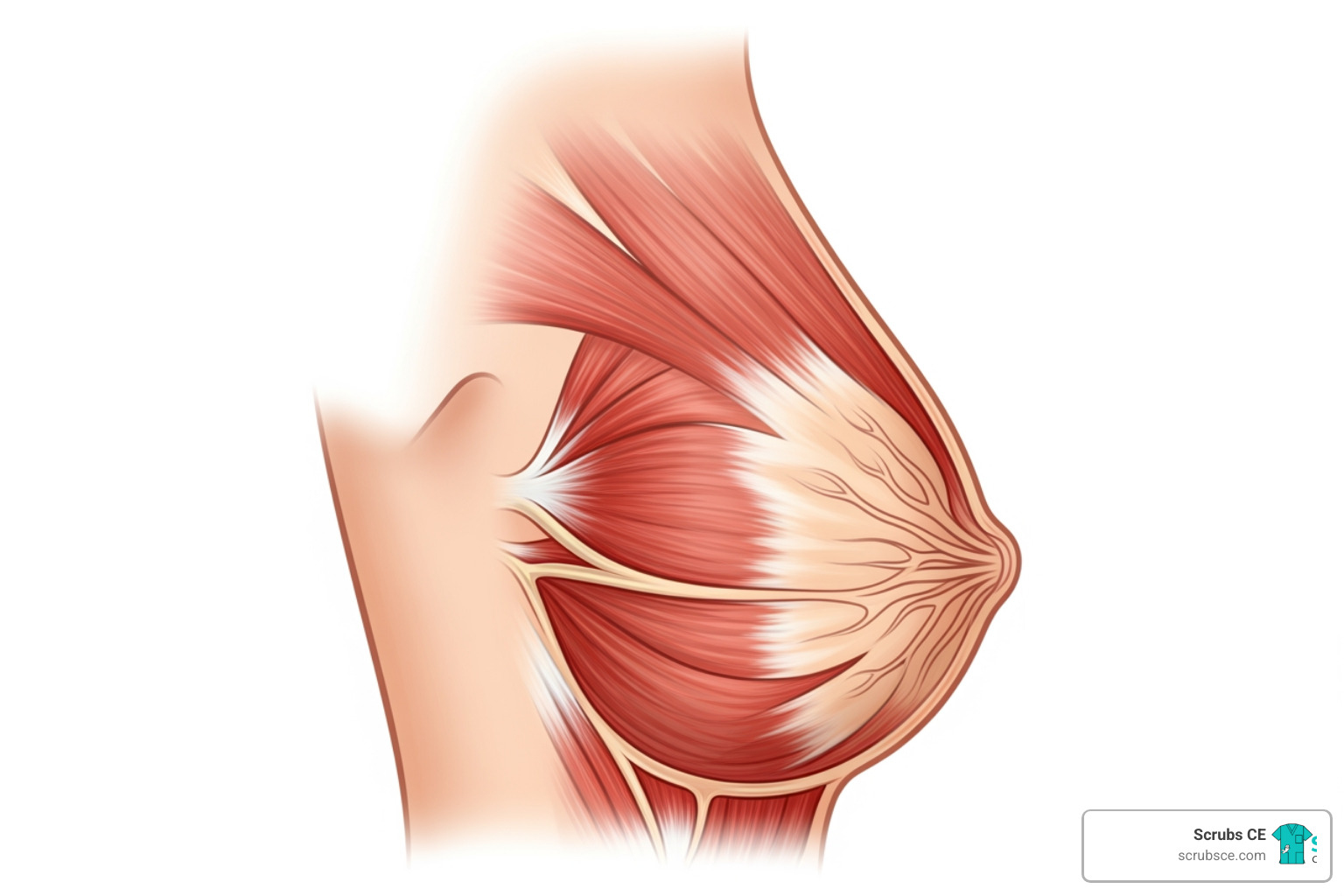

Key Elements of MLO Mammography Positioning Techniques

The MLO view is arguably the single most useful mammographic projection. It provides the greatest amount of coverage for a single projection, visualizing breast tissue from the axillary tail down to the inframammary fold (IMF). Our goal with the MLO is to capture the maximum amount of breast tissue, especially the deep tissues near the chest wall, which can be prone to cancer development.

Here’s how we achieve an optimal MLO view:

- Pectoralis Muscle Visualization: This is a critical landmark. The pectoralis muscle should be visible, wide at the top, and tapering as it crosses behind the upper breast. Its anterior convex border should extend to the Posterior Nipple Line (PNL) or below. We want its lower edge to be at or below the PNL, which is an imaginary line drawn from the nipple towards the pectoralis muscle. If the pectoralis shadow isn’t seen, or its lower edge is above the PNL, we know we’ve missed crucial posterior tissue. In fact, statistics show the lower edge of the pectoralis was above the pectoralis–nipple line in 2.081% of MLO views.

- Inframammary Fold (IMF) Open: The IMF, the crease where the breast meets the chest wall, must be open and clearly visible. This ensures we haven’t cut off any inferior breast tissue. If the IMF isn’t visualized, we might be missing masses in this area, which accounts for 1.189% of MLO view errors.

- Posterior Nipple Line (PNL): This line, measured from the base of the nipple to the pectoralis muscle, is our yardstick for posterior tissue inclusion. Ideally, it should intersect the pectoralis muscle at a perpendicular angle. We’ll compare this measurement to the CC view later.

- Gantry Angulation: The gantry, the part of the mammography unit that holds the X-ray tube and detector, needs to be angled to match the patient’s pectoralis muscle. This typically ranges from 40 to 60 degrees. For taller patients, we might use a higher angle, and for shorter patients, a lower one. The average angulation is 50 degrees.

- “Up and Out” Breast Lift: This is our secret weapon! We gently lift the breast “up and out” from the chest wall and pull it forward and medially. This maneuver gathers deep lateral tissues and helps open the IMF, preventing it from overlapping with the upper abdomen. It also helps prevent the dreaded “camel’s nose” effect, where the breast droops, creating a fold.

- Patient Leaning and Arm Placement: We ask the patient to lean into the machine, relaxing their shoulder to avoid tension in the pectoralis muscle. Their arm should be draped over the top of the detector, with the elbow bent and relaxed. This helps us pull more breast tissue into the field of view.

- Capturing Axillary Tail: The detector should be placed high and deep into the axilla to ensure we capture the entire breast, including the axillary tail, which can harbor cancerous lesions. Inadequate coverage of lower quadrants was noted in 2.787% of MLO views, emphasizing the need for meticulous positioning.

Key Elements of CC Mammography Positioning Techniques

The CC view complements the MLO by providing a top-to-bottom perspective, which is particularly good for visualizing the far medial and posterior aspects of the breast, areas often excluded in MLO views. This view is crucial for detecting abnormalities in the upper portion of the breast and well depicts central and subareolar areas.

Here’s how we ensure a technically adequate CC view:

- Nipple in Profile: We aim to have the nipple in profile, centered and pointing straight towards the back of the receptor. This helps prevent it from mimicking a retroareolar mass. However, maximizing tissue coverage always takes precedence over the nipple being perfectly in profile. Improper positioning of the nipple was the commonest problem, seen in 3.827% of mammograms in the CC view, so attention to detail here is vital.

- Posterior Tissue Inclusion: Our goal is to pull as much posterior breast tissue as possible onto the detector. We achieve this by standing on the medial side of the breast, pulling the breast up and away from the chest wall, and ensuring the compression paddle is firmly against the chest wall. We also lift the IMF to bring more tissue into the field.

- Mobile-to-Fixed Margin Technique: We position the breast by pulling it from its mobile margins (lateral and inferior) towards its fixed margins (medial and superior). This helps gather more tissue.

- IMF Elevation: We gently lift the inframammary fold, which allows more breast tissue to be pulled onto the image receptor.

- Patient Height Adjustment: We adjust the height of the mammography unit so the patient can comfortably lean into the machine with their feet slightly forward and hips back.

- Visualizing Medial and Lateral Tissue: The CC view is excellent for demonstrating whether lesions are medial or lateral to the nipple. It’s especially important for medial tissue, as this area is often not fully demonstrated on the MLO view. We also pull lateral posterior breast tissue onto the detector to maximize glandular tissue visualization.

- PNL Measurement Comparison to MLO: We measure the PNL on the CC view (from the base of the nipple to the posterior edge of the image) and compare it to the MLO view. Ideally, these measurements should be within 1 cm of each other. A mismatch in Pectoralis–Nipple Distance (PND) was seen in 3.864% of mammograms, highlighting the importance of this comparison. This ensures we’ve captured adequate posterior depth.

Assessing Technical Adequacy: Are Your Images ACR-Ready?

Achieving technically adequate mammograms isn’t just about following steps; it’s about adhering to rigorous quality standards set by organizations like the American College of Radiology (ACR). These guidelines are our benchmark for excellence, ensuring that our images are of diagnostic quality and can effectively aid in early breast cancer detection. Quality control and self-assessment are continuous processes. We constantly evaluate our work, seeking to identify and correct common positioning errors before they lead to serious consequences.

It’s a challenging endeavor. Even after ACR positioning training, only 67% of images would meet ACR criteria. This statistic underscores the complexity of our work and the need for ongoing education and meticulous practice. Mistakes in positioning were recognized in 2.879% of total mammograms in one study, demonstrating that these issues are not uncommon.

The consequences of positioning errors are severe:

- Missed Diagnoses: If a lesion isn’t captured on the image, it cannot be diagnosed. This directly impacts early detection and patient outcomes.

- Increased Recalls: Suboptimal images often lead to patient recalls for additional views or diagnostic mammograms, causing unnecessary anxiety, inconvenience, and additional radiation exposure.

- Reduced Sensitivity: Poor positioning reduces the overall sensitivity of mammography, making it less effective as a screening tool.

To dig deeper into the impact of these errors, you might find this scientific research on positioning mistakes insightful.

Evaluating the MLO View

When we evaluate an MLO view, we’re looking for several key indicators of technical adequacy:

- Pectoralis Muscle Criteria:

- It should be wide at the top and taper down, indicating proper inclusion of axillary tissue.

- Its anterior border should be convex or straight, not concave, which would suggest muscle tension or incorrect positioning.

- Crucially, the pectoralis muscle should extend down to or below the Posterior Nipple Line (PNL). If the lower edge of the pectoralis is above the PNL, we’ve missed posterior tissue (2.081% of MLO views).

- Open Inframammary Fold (IMF): The IMF must be clearly visualized and open, free of any skin folds or overlap with abdominal tissue. If the IMF is not visualized (1.189% of MLO views), we risk missing lesions in the inferior breast.

- Absence of Skin Folds: While some skin folds in the lower breast are common (demonstrated in 49% of all MLOs), excessive or obscuring folds can hide pathology. We strive to minimize these.

- Breast Not Sagging: The breast should appear well-supported and lifted, not drooping or showing a “camel’s nose” effect, which can happen if compression is released too soon or the breast isn’t adequately supported.

- PNL Measurement: We ensure the PNL is adequately measured, providing a baseline for comparison with the CC view.

Evaluating the CC View

For the CC view, our checklist includes:

- Nipple Centered and in Profile: The nipple should ideally be centered and in profile, pointing straight back. Improper nipple positioning was the commonest problem, seen in 3.827% of mammograms in the CC view, often leading to artifacts or confusion with a lesion.

- Visualization of Posterior Tissue: This is assessed by comparing the PNL on the CC view to that on the MLO view. We aim for these measurements to be within 1 cm of each other. A significant mismatch (seen in 3.864% of mammograms) indicates that we haven’t captured enough posterior tissue on the CC view.

- Pectoralis Muscle Seen: While not always required, the pectoralis muscle can be seen on approximately 30% of properly positioned CC views, especially in the lateral aspect. Its presence indicates excellent posterior tissue inclusion.

- Absence of Skin Folds: Just like in the MLO, minimizing skin folds is important to prevent obscuring breast tissue.

- PNL within 1 cm of MLO view: This critical comparison ensures consistent capture of posterior breast depth across both standard views.

Advanced Mammography Positioning Techniques for Common Challenges

Not every patient fits the “standard” mold, and that’s where our expertise truly shines. Patient body habitus, physical limitations, and even their emotional state can present unique challenges. In these situations, communication is key, and we must be prepared to tailor the exam to ensure optimal imaging while prioritizing patient comfort and safety. As we often say, “You can’t get ACR ‘perfect’ images on every patient, and all good radiologists should understand this!”

For those interested in pushing the boundaries of their knowledge, exploring advanced breast imaging techniques is a great next step.

Positioning for Breast Implants

Breast implants present a unique challenge, as they can obscure underlying breast tissue and interfere with compression. Our goal is to visualize as much native breast tissue as possible.

We achieve this through:

- Standard Implant-in-Place Views: First, we obtain standard MLO and CC views with the implant included. For these views, we use lighter compression to avoid rupturing the implant.

- Implant Displaced (ID) Views (Eklund Technique): This specialized technique is crucial for visualizing breast tissue effectively. We gently push the implant back against the chest wall, out of the field of view, and apply normal compression to the breast parenchyma anterior to the implant. This allows us to better evaluate the breast tissue itself. The Mammographic Quality Standards Act (MQSA) recommends two additional views of each breast in addition to the standard views for patients with breast augmentation.

Overcoming Anatomical and Physical Problems

Here are some specific techniques and adjustments we use to overcome common positioning problems:

- Large or Pendulous Breasts:

- Mosaicking/Tiling: For extremely large breasts that exceed the detector size, we might use multiple overlapping images (mosaicking or tiling) to cover the entire breast. When doing this, we try to include the lateral breast on CC views first, and the medial breast on one CC view.

- Lower Angulation for MLO: For MLO views, a lower degree of angulation (e.g., 40 degrees) can sometimes counteract gravity and provide better support, preventing the breast from falling away.

- “Push Up” Technique: We push the breast higher than we think we need to for MLOs, even if it creates an axillary crease. This helps ensure maximum glandular tissue is included.

- Contralateral Breast Lift: We have the patient lift and flatten her contralateral breast to help open the IMF and eliminate unwanted folds on the breast being imaged.

- Hold Until Compressed: We don’t let go of the breast until it’s completely compressed to avoid the “camel’s nose” effect or inferior nipple rolling, especially in obese patients where inadequate compression can cause the nipple to roll inferiorly.

- Small Breasts:

- Spatula Technique: For very small breasts, especially in the CC view, it can be hard to pull enough posterior tissue onto the detector. We can use a rubber spatula to gently hold the posterior breast tissue on the image receptor during compression.

- Half-Paddle: If available, a specialized half-paddle can be used to compress smaller areas more effectively without hitting the patient’s hand.

- Slouching for MLO: For mediolateral views, asking the patient to slouch can help breast tissue fall forward, making it easier to position.

- Patients in Wheelchairs:

- Equipment Adjustments: We remove wheelchair arms and foot supports whenever possible.

- Upright Positioning: We position the patient as upright and forward as possible, using pillows or sponges for support if needed.

- C-arm Rotation: For MLO views, we can bring the wheelchair in at a 45-degree angle. For CC views, “lordotic” CCs (where the patient leans back) can be helpful. Flipping the unit 180 degrees and bringing compression from below can also work for kyphotic patients in wheelchairs.

- Limited Mobility/Frozen Shoulder:

- Arm Placement: For MLOs, instead of forcing the arm up, we can lift the patient’s axilla over the corner of the IR and allow the arm to hang freely behind the IR.

- Sliding Technique: If the patient cannot lift their arm, we ask if they can bring it forward and slide it back, rather than lifting it 90 degrees. The compression paddle edge can help hold the arm back. A lateral medial (LM) view, which takes advantage of breast mobility, is often preferred here.

- Prominent Abdomens or Kyphosis:

- Patient Posture: For prominent abdomens, we ask the patient to stand two hands’ width away from the image receptor and bend forward as if picking something up. This brings their chest forward, allowing the abdomen to lean back and the breast tissue to be positioned.

- Additional Views: An additional lower MLO view focusing on the IMF or a Lateral Medial (LM) view can be performed to ensure full coverage of the inferior breast tissue, which can be obscured by a prominent abdomen.

- Kyphosis: For kyphotic patients (hunched back), we can flip the unit 180 degrees, place the image receptor at the superior aspect of the breast, and bring compression up from below. A reverse oblique view (LMO) is often better than a regular MLO.

The Critical Role of Compression and Communication

Compression is the unsung hero of mammography. It’s not just about holding the breast still; it’s a multifaceted technique vital for image quality and diagnostic accuracy. Compression helps in:

- Reducing Motion Artifact: By immobilizing the breast, compression eliminates blur caused by patient movement.

- Spreading Tissue: It spreads out overlapping breast structures, making it easier to identify subtle lesions that might otherwise be hidden.

- Uniform Thickness: Compression creates a more uniform thickness of the breast tissue, which allows for consistent X-ray penetration and better image contrast.

- Lowering Radiation Dose: A thinner breast requires less radiation to penetrate, thus reducing the patient’s dose.

But even the best compression won’t work without patient cooperation, which hinges on effective communication. Explaining the procedure and building patient trust are paramount. As we discuss in our mammography CE topics, patient comfort is crucial for accurate imaging.

Compression Best Practices

- Firm but Tolerable: We apply compression until the breast tissue is taut, or the patient indicates discomfort. The goal is firm, not painful, compression. Interestingly, the average pressure generated is about 3 psi, less than the 6 psi from a clinical breast exam!

- Smart Paddle Technology: Modern machines often have smart paddles or patient-controlled compression, which studies suggest can reduce discomfort.

- Observing Tissue Tautness: We visually check for tautness of the skin, indicating adequate compression.

- Holding Compression: We maintain compression until the exposure is complete. Releasing too soon can lead to the “camel’s nose” effect or inferior nipple roll.

- Avoiding the “Camel’s Nose” Effect: This occurs when the breast sags or folds due to inadequate support or premature release of compression, leading to excluded tissue. We actively prevent this by holding the breast “up and out” until full compression is achieved.

- Slow Compression Rate: A slower compression rate appears to be preferred by patients over rapid squeezing.

Communication Strategies for Challenging Patients

Working with patients who have physical limitations or anxiety requires a compassionate approach:

- Explaining Each Step: We explain exactly what we’re doing before we do it. This manages expectations and reduces anxiety.

- Calm and Reassuring Tone: Our demeanor sets the tone for the exam. A calm, empathetic voice can make a world of difference.

- Asking for Feedback on Comfort: We constantly check in with the patient, asking “Is this okay?” or “Tell me if this hurts.” We assure them we can stop or adjust if needed.

- Providing Clear Breathing Instructions: Simple instructions like “hold your breath” ensure a still image and minimize motion artifact.

- Documenting Limitations: This is perhaps one of the most critical steps. If we can’t achieve a perfect image due to patient limitations (e.g., kyphosis, frozen shoulder, prominent abdomen), we document it clearly and in appropriate terminology for the radiologist. This helps them understand why an image might be compromised and prevents unnecessary recalls. We’ve often seen how general radiology images (like portable CXRs in the ICU) are accepted with limitations, yet mammography often faces unrealistic expectations. Documenting these challenges fosters better understanding between technologists and radiologists.

Frequently Asked Questions about Mammography Positioning

Why is the pectoralis muscle so important on an MLO view?

The pectoralis muscle serves as a critical landmark to ensure that the posterior breast tissue, located closest to the chest wall, has been included in the image. An adequately visualized pectoralis muscle, extending to or below the posterior nipple line, indicates a comprehensive view and reduces the chance of missing deep lesions. If the pectoralis muscle is not adequately visualized, it suggests that valuable posterior tissue may have been excluded, potentially hiding a cancer.

What is the most common positioning error and how can I avoid it?

Statistics show improper nipple positioning is a frequent issue, especially in the CC view (3.827% of CC views). To avoid this, ensure the nipple is in profile and pointing straight out on the CC view, and not rolled on the MLO view. This requires careful manipulation of the breast as it’s placed on the receptor and just before compression is applied. We often gently pull the breast forward and slightly medially for the CC view to ensure the nipple is in profile without sacrificing posterior tissue.

How do I know if I’ve captured enough breast tissue on the CC view?

A key quality check is to measure the Posterior Nipple Line (PNL) on your CC view and compare it to the MLO view. The CC measurement should be within 1 centimeter of the MLO measurement. This confirms that you have successfully imaged the posterior depth of the breast from top-to-bottom. If there’s a significant mismatch (greater than 1 cm), it suggests that posterior tissue was missed on the CC view, and an additional view might be necessary.

Conclusion

Mastering mammography positioning techniques is a continuous journey, a blend of scientific knowledge, technical skill, and empathetic patient care. It’s an art form that directly impacts patient outcomes, making us crucial players in the fight against breast cancer. The ability to adapt to diverse patient anatomies and overcome complex challenges is what defines an exceptional mammography technologist.

We’ve explored the foundational CC and MLO views, digd into the metrics of technical adequacy, and armed ourselves with advanced strategies for challenging patients. We’ve also highlighted the critical roles of compression and communication, reminding ourselves that every patient deserves our best effort and understanding.

The field of mammography is changing, and our commitment to lifelong learning is essential. We encourage you to continuously refine your skills, stay updated on advancements, and engage in ongoing education. Your expertise makes a significant difference in the quality of care provided and, ultimately, in saving lives.

To further improve your skills and stay at the forefront of mammography, we invite you to explore our comprehensive Mammography CE Courses. Let’s continue to strive for that perfect picture, every time.

Recent Comments